Update(MM/DD/YYYY):10/30/2015

Elucidation of the Unique Mechanism for Symbiont Acquisition in Stink Bugs, a Group of Notorious Pest Insect

– Stink bugs screen symbiotic bacteria inside the gut –

Points

-

Discovery of a specific organ for screening bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract in stink bugs

-

The gastrointestinal tract of stink bugs is functionally divided in the middle by the constricted region

-

Possible contribution to the development of a new method to control pest insects by inhibiting gut symbiotic associations

Summary

Yoshitomo Kikuchi (Senior Researcher and also Visiting Associate Professor of the Research Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University) of the Environmental Biofunction Research Group, the Bioproduction Research Institute (BPRI; Director: Tomohiro Tamura), the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST; President: Ryoji Chubachi), Takema Fukatsu (Prime Senior Researcher and Leader of the Symbiotic Evolution and Biological Functions Research Group) of BPRI, AIST, and Tomoyuki Hori (Senior Researcher) of the Environmental Microbiology Research Group, the Environmental Management Research Institute (Director: Mikiya Tanaka), AIST, and others, in collaboration with Kozo Asano (Specially Appointed Professor) and Tsubasa Ohbayashi (2nd grade graduate student) of the Research Faculty of Agriculture, and others of Hokkaido University (President: Keizo Yamaguchi), the Open University of Japan, National Institute for Agro-Environmental Science, and Pusan National University in Korea, have shown that stink bugs, known as agricultural pests, select only a specific symbiotic bacterium among various bacteria ingested with food by the narrow segment developing in their gastrointestinal tract, and take the bacterium into their symbiotic organ.

The present results have elucidated for the first time a unique mechanism involved in acquiring specific symbiotic bacteria, which is a characteristic shared by diverse stink bugs, a kind of pest insect, and are expected to lead to the development of a new method for controlling pest insects by inhibiting the establishment of gut symbiosis.

The results will be published online in a US academic journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, on September 1, 2015 (Japan Time).

|

A female bean bug, Riptortus pedestris (left), and the gastrointestinal tract of a bean bug fed with a food dye (right)

While the dye stops at the constricted region located at the middle of the gastrointestinal tract (yellow arrow), symbiotic bacteria pass through and infect the symbiotic organ. |

Social Background of Research

Almost all “pest insects” such as agricultural pests that damage crops, sanitary pests that transmit pathogenic microorganisms, and household pests such as termites that damage wooden houses, commonly possess symbiotic bacteria in their bodies. These bacteria play a role in supplying the nutrients necessary for growth, living, and breeding, and/or assist in digestion of food materials. Since the symbiotic bacteria could be a new target for controlling pest insects, various research has focused on elucidating the mechanism(s) for establishment of the symbiotic associations.

With regard to stink bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroneura), more than 40,000 species in the world and 1,500 species or so in Japan are known, many of which are serious agricultural pests. Few studies have thoroughly examined such a large number of species, their ecological aspects are not well understood, and therefore the pest insects are difficult to control, damaging various agricultural crops such as rice and soybean; a method of controlling them is demanded. Many of the plant sap-sucking stink bugs harbor symbiotic bacteria in their gut, which play an important role in supplying nutrients, adapting to plant hosts, and retaining insecticide resistance. Although knowledge has been accumulated regarding the function and evolution of symbiotic bacteria, the mechanism for establishment of the specific gut symbiosis in the stink bugs is not well understood.

History of Research

AIST discovered that the bean bug Riptortus pedestris, a serious pest of soybean, has a unique system of gut symbiosis. Although symbiotic bacteria are transmitted directly from mother to offspring in most insects, in the bean bug, a new symbiotic relationship is established for respective generations by their nymph’s oral ingestion of symbiotic bacteria called Burkholderia which inhabit environmental soil. Since Burkholderia are easy to cultivate and can be genetically modified, they have attracted research interest to elucidate the genetic background involved in the symbiotic association.

With respect to the gut symbiotic system of the bean bug, AIST has achieved research results such as “Discovery of Symbiotic Bacteria Mediating Insecticide Resistance to Pest” (AIST press release on April 24, 2012) and “Novel Biological Function of Polyester in Insect-Bacterium Symbiosis” (AIST press release on June 11, 2013).

Hokkaido University has a cooperative graduate school with AIST, under which research of the bean bug has been conducted with graduate students, and has advanced development of excellent human resources such as a Hokkaido University graduate student winning the Best Poster Award of an international conference (Hokkaido University press release on September 25, 2014). The present research has been conducted by Tsubasa Ohbayashi and others, who are Hokkaido University graduate students, under the mentorship of Yoshitomo Kikuchi (Senior Researcher) of AIST.

This research was supported by the “Program for the Promotion of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Industry and Food Industry Science and Technology Research” of the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Council of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and the “Endowed Courses Subsidy” of the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka.

Details of Research

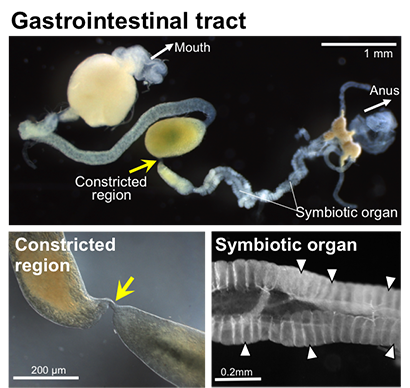

The bean bug has a large number of sac-like tissues in the posterior half part of the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 1), where Burkholderia colonize symbiotically. The researchers have called this gastrointestinal tract region, where a large number of sac-like tissues develop, a “symbiotic organ.” In addition, as the gastrointestinal tract becomes very narrow near the middle (the site located anterior to the symbiotic organ), the researchers named this site “constricted region” (Fig. 1) in this research. The constricted region was described in previous studies, but its function was unknown.

|

|

Figure 1: Whole image of the gastrointestinal tract and enlarged images of the constricted organ and the symbiotic organ of a bean bug |

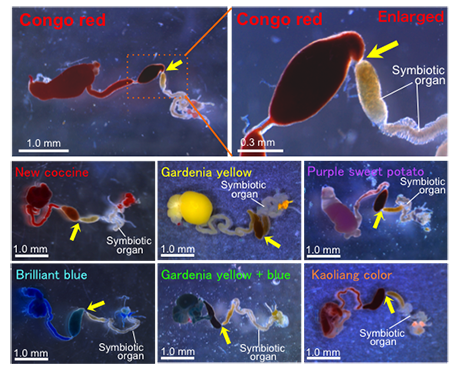

First, in order to clarify the food flow in the gastrointestinal tract of the bean bug, the researchers observed the flow path of the contents of the gastrointestinal tract after feeding bean bugs with various food dyes. They found that, even though the dye reached the constricted region, the dye never flowed beyond the constricted region into the symbiotic organ (Fig. 2), indicating that the inflow of food was extremely restricted at this constricted region of the gastrointestinal tract.

|

|

Figure 2: Gastrointestinal tracts of bean bugs fed with various dyes (The yellow arrows indicate the constricted region.) |

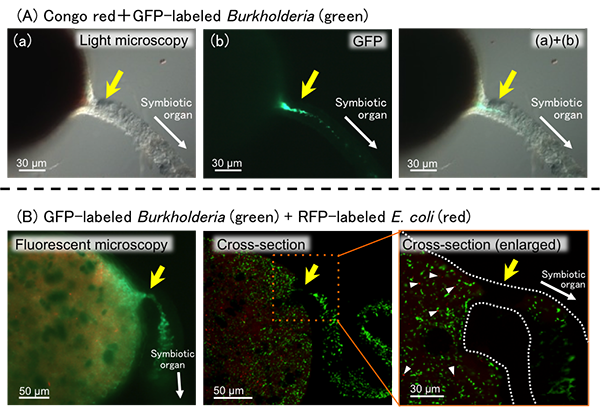

Next, the researchers orally inoculated bean bug nymphs having no Burkholderia symbiont with both a food dye and Burkholderia labeled by green fluorescent protein (GFP), and found that the food dye stopped at the constricted region and only Burkholderia passed through the region and enter into the symbiotic organ (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, in bean bug nymphs fed with both the GFP-labeled Burkholderia and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-labeled E. coli, whereas the E. coli stopped at the constricted region, only the Burkholderia passed through it and reached the symbiotic organ (Fig. 3B). Besides E. coli, in bean bug nymphs orally inoculated with Pseudomonas putida and Bacillus subtilis that are typical soil bacteria, neither of the bacteria infected the symbiotic organ. Based on these findings, the researchers conclude that the bean bug has sophisticated bacterium-screening machinery in its gastrointestinal tract, which allows symbiotic bacteria specifically to pass through while restricting the inflow of substances.

Based on the fact that the food dyes were detected in the Malpighian tubule and feces, it is considered that all the digestion and absorption of food materials is accomplished before the constricted region and the dye absorbed into body fluid was gathered in the Malpighian tubule and excreted. In short, the gastrointestinal tract of bean bugs has two functionally distinct parts, an “anterior part to digest and absorb feed” and a “posterior part to harbor symbiotic bacteria,” with the constricted region in the middle of it. Although the restriction of feed inflow half way through the gastrointestinal tract like this has not been reported in the case of ordinary animals, it is likely to be related to the fact that bean bugs feed on plant sap, which is easy to digest and absorb.

|

Figure 3: Screening of symbiotic bacteria at the constricted region

(A) Enlarged images of the constricted region when a bean bug was fed with both a dye and GFP-labeled Burkholderia

(B) Enlarged images of the constricted region when a bean bug was fed with both GFP-labeled Burkholderia and RFP-labeled E. coli. The right two photos are cross-section images observed by a confocal microscope. The yellow arrows indicate the constricted region. |

Second, in order to elucidate the mechanism by which Burkholderia pass through the constricted region, the researchers produced transposon-generating mutants of Burkholderia and screened mutant strains that cannot colonize in the gut symbiotic organ. The results revealed that the non-motility strains having transposon-insertions in flagella formation genes could not pass through the constricted region. This strongly suggests that Burkholderia pass through the constricted region by flagellar mortality.

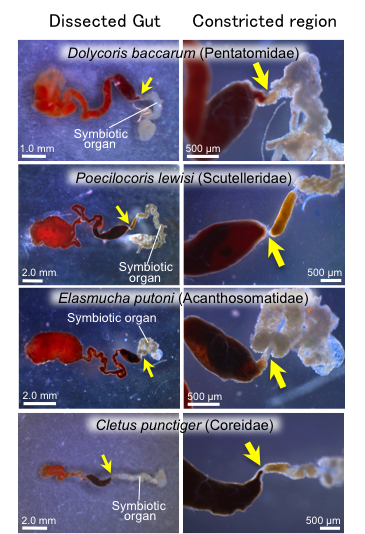

A number of stink bug species, which are crop-damaging pest insects, possess gut symbiotic bacteria, as shown in the bean bug. Observation of the gastrointestinal tract of stink bug species of diverse taxonomic groups revealed that there was a constricted region near the middle of the gastrointestinal tract as is the case with the bean bug. The stink bug species were fed with a food dye to confirm the flow path, revealing that the dye stopped at the constricted region and never flowed into the symbiotic organ in all of the species investigated (Fig. 4). Based on these results, it is considered that the gastrointestinal tract has two functionally distinct parts, an “anterior part to digest and absorb feed” and a “posterior part to harbor symbiotic bacteria” and symbiotic bacteria are screened through the constricted region in the stink bug species, which seems to be a common feature among diverse stink bug species.

|

|

Figure 4: Gastrointestinal tracts of diverse stink bugs fed with a food dye (The yellow arrows indicate the constricted region) |

Future Plans

The researchers intend to analyze expressed genes and proteins in the constricted region that is the bacteria-screening organ, focusing on the bean bug, and try to reveal the genetic basis of the sophisticated gut screening of symbiotic bacteria.

Since the symbiont screening by the constricted region is a common mechanism in most stink bug species, a kind of pest insect, elucidation of the genetic basis could lead to the development of a new pest control technology for preventing infection and colonization of symbiotic bacteria. From this viewpoint, the researchers will pursue their research.